(3) Thirst for Justice - continued

(3.3)

Dioscorus’s seven years in the capital city of Upper Egypt were productive

creatively. The general consensus is that most of his encomia and epithalamia

were composed there. Antinoöpolis, founded during the reign of Hadrian, was

second in importance only to Alexandria. It was not only a cultural center, but

also the residence and administrative center of the duke. In 539, according to

Justinian’s Edict XIII, the two provinces of Upper Thebaid and Lower Thebaid

were put under the jurisdiction of one office, the dux Thebaidis. The duke, who also carried the title of Augustalis, had both civil and military

authority. It has been assumed by most scholars that Dioscorus wrote his poems

in praise of several dukes and members of their staffs in order to advance his

career and financial situation. Maspero stated this assumption already in his

critical essay of 1911, and interpreted verses in several poems as undisguised

requests for money. Perhaps there was more at work in these poems.

"Arable." Near Kom Ishqaw (Aphrodito), Egypt. Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn

(3.4)

Before leaving Antinoöpolis, Dioscorus drafted yet another petition for an

embassy of Aphroditans, complaining of new outrages committed by the pagarch.

The petition is addressed to an unnamed new duke, and states that the previous

tax rate for the village’s arable land and vineyards (two carats per aroura and

eight carats per aroura, respectively) had been raised by the pagarch Julian.

Julian then promised that no further tax increases would be made. This

agreement was not kept and the taxes were raised. When owing to the failure of

the inundation the new taxes could not be met, Julian made an agreement that he

would be content with payment at the old tax-rate. Yet then with a gang of

followers, the pagarch inexplicably attacked the village. He committed many

outrages, including violating the women religious. The petition suggests that

these activities by the pagarch were in disregard of the duke, who had granted

Aphrodito a remission of taxes. To confirm the truth of their statements in the

petition, the villagers took an oath in the monastery of Apa Macrobius “in the presence of the saints” (P.Lond.

V 1674, line 73). The Aphroditans further confirm the truth of their statements

by a written oath to God and to Christ the King of Kings (lines 83-84).

(4) Return to Aphrodito

"Transportation." Kom Ishqaw (Aphrodito), Egypt. Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn

(4.1)

Before May of 574, Dioscorus had returned to Aphrodito. The reason for his

return is nowhere made clear. H. I. Bell suggests that a new duke was finally able—or

wanted—to control the pagarch’s aggression. Perhaps his return was again

related to events in Constantinople. Although in 565 Justin II had tried to

reconcile himself to the Monophysites, in 571 he launched a savage persecution

and by 573 he was completely insane. Dioscorus, if a Monophysite, would now have

seen a bleak outlook to advance his career at the court of the duke. Whatever the reason for returning to his

village, Dioscorus appears to have withdrawn from legal and political

activities. He composed a contract for the monk Psates from the Monastery of

Apa Apollos. The monk was donating a house, and money to enlarge the house, in

order to provide a residence for visiting monks. The rest of the documents

after Dioscorus’s return were made primarily for mundane rural activities:

receipts and disbursements of grain, seed grain, chickpeas, mud for bricks, etc.

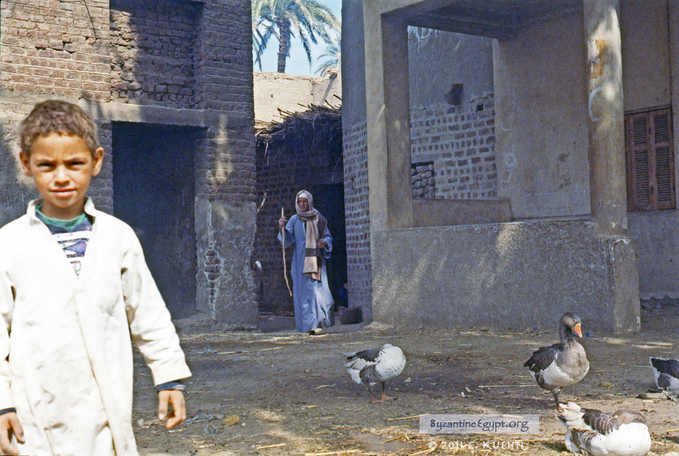

"Boy and Gooseherd." Kom Ishqaw (Aphrodito), Egypt. Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn

(4.2)

Creatively, however, Dioscorus was very productive. His two elaborate encomia to John (Heitsch 2 and 3, Fournet

20 and 11) are assigned by MacCoull to the post-Antinoöpolite years.

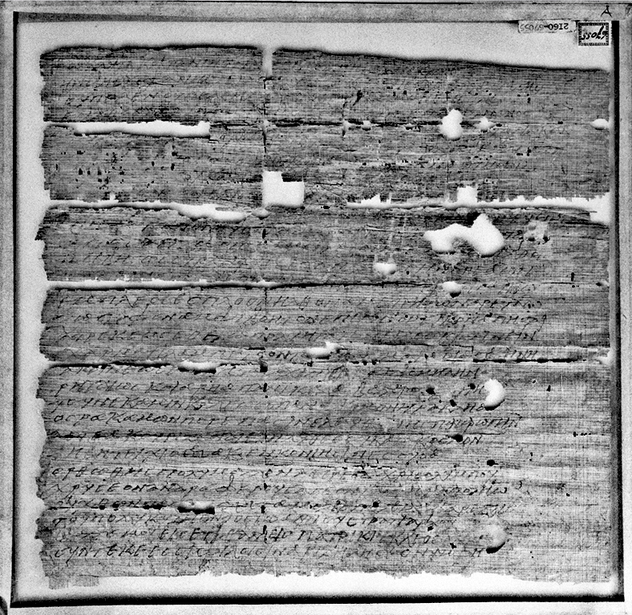

P.Cair.Masp. I 67055 verso (= Heitsch 2, Fournet

20). A poem addressed to John,

written on the back of an account. Photo © 2011 C. Kuehn

written on the back of an account. Photo © 2011 C. Kuehn

It is also

likely that the many creative works on the verso of P.Cair.Masp. I 67097, including the complex and subtle masterpiece

“verso F,” were also composed then. Since many of his poems were written on

the backs of documents that had been produced in Antinoöpolis and brought back to

Aphrodito, even more poetry might have been composed not in the capital but in

the village. His last dated document is a contract entered into an eight-page

account book written in his hand. Although the accounts seem to come from a few

years earlier, a land lease recorded on one of the leaves bears the date of 5

April 585. And here the archive of Dioscorus of Aphrodito and all we know of

his practical affairs come to an end.

"Gooseherd." Kom Ishqaw (Aphrodito), Egypt. Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn

Dioscorus was the descendant of a certain Psimanobet , which means "the gooseherd's son".

Dioscorus was the descendant of a certain Psimanobet , which means "the gooseherd's son".