I BYZANTINE PAPYRUS

DISCOVERY AND DISPERSAL

(1) Discovery

(1.1)

In July of 1905, Gustave Lefebvre had been Inspector in Chief of the

Antiquities Service of Egypt for barely six months. Suddenly a man from Tima, about four hundred kilometers south of Cairo, informed

him of a new find of papyrus at the village of Kom Ishqaw (or Ashkaw, the modern names for Aphrodito).

"Rider with Roll." Kom Ishqaw (Aphrodito), Egypt. Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn

Part of an old wall of a house had collapsed and revealed a chasm below. At the bottom of this crevice were seen numerous rolls of papyrus. By the time Lefebvre arrived, however, the rolls were gone. What fragments remained were torn apart and mutilated. The rest had probably been distributed among the villagers and concealed. Yet when the remaining fragments, filled with Coptic and Greek writing, were removed from the crevice, Lefebvre noticed what seemed to be verses of a Greek comedy. These 120 verses proved to be a fragment of a fourth- or fifth-century A.D. codex of the comedy Demes by Eupolis. Very little by this Athenian comedy writer from the fifth century B.C. had survived to the modern era. These verses gave Lefebvre hope of still finding something valuable.

(1.2) The houses were too close together to excavate between, so he asked the village headman to inform him as soon as anyone in the neighborhood made plans to demolish a house.

"Close Quarters." Kom Ishqaw (Aphrodito), Egypt. Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn

By the end of the same year the owner of the collapsed wall decided to tear down and rebuild his home. Gaston Maspero, Director of the Antiquities Service of Egypt, gave Lefebvre the authorization; and for a few pounds the owner of the house gave permission to excavate his property all the way to the street.

(1.3) Lefebvre began immediately. After only one meter of digging, he uncovered ancient walls of unbaked brick. There had been a roof, of which the first few courses were still visible. The walls continued down for another two meters and demarcated three rooms. It was a medium-sized house, which had been built during the Roman period (30 B.C. - A.D. 300). In the corner of one small room, which had an area of no more than one and a half square meters, stood a large jar which was shattered down to its neck. It was now about .90 meter tall. Spread out around the jar in the sebakh ("rich soil," often found around ancient sites) lay papyrus rolls and fragments that had escaped from the container. The jar itself was filled with more papyrus, on top of which lay eleven leaves (twenty-two pages) of a fifth-century codex (“book”) of Menandrian comedies. In the sebakh were found six more leaves of the same codex, thus making a total of thirty-four pages containing more than 1300 verses—all from an author whose works had virtually disappeared during the Middle Ages. This fourth-century B.C. author, Menander (Comicus), had been held in the highest esteem during the Hellenistic, Roman, and early Byzantine periods. In fact, he was considered second only to Homer in poetic excellence. Yet during the fourteenth century, the monks of Constantinople condemned his comedies and burned his manuscripts. From the Renaissance to the beginning of the twentieth century all that remained were his astounding reputation and a few excerpted sententiae. Discoveries of papyrus fragments by Nicole, Jouguet, and Grenfell and Hunt increased somewhat the size of his surviving oeuvre. But the leaves of the codex which Lefebvre now held in his hands were—in his own words—“without argument, the most important which have been discovered to this day.”

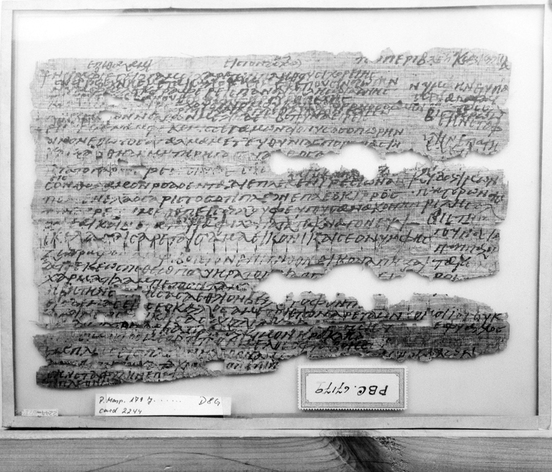

P.Cair.Masp. II 67179 recto (= Heitsch 21, Fournet

32 A). This poem was composed

to celebrate the wedding of Callinicus. It is written in Greek, the literary language

of Egypt in the Byzantine Era (A.D. 300 - 700). Photo © 2011 C. Kuehn

to celebrate the wedding of Callinicus. It is written in Greek, the literary language

of Egypt in the Byzantine Era (A.D. 300 - 700). Photo © 2011 C. Kuehn

(1.4) Beneath this codex had been stored about one hundred and fifty papyrus scrolls, containing primarily personal, legal, and government documents. Many of these documents, as though they had been considered scrap paper, had poems written on their versos (“backs”). These poems were in Greek; and because of the corrections and revisions, they appeared to be original compositions. Lefebvre noted that the Menandrian codex had been used as a sort of cork to close the jar and protect the papyri beneath, as though for the owner the latter had been more important.

(1.5) Gustave Lefebvre returned to excavate at the same site in 1906 and 1907, but found little more of value. He then brought what he had found to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. There Lefebvre quickly edited the Menandrian codex. Jean Maspero, the young son of the Director of the Antiquities Service, edited the other Greek papyri. These scrolls and fragments filled three volumes, which are now referred to as P.Cair.Masp. I, II, and III. Jean published the first two volumes in 1911 and 1913; Jean’s father, Gaston, published the third volume in 1916, after his son had died in battle. At the time of death, Jean was only twenty-nine.

"Rubble." Kom Ishqaw (Aphrodito), Egypt. Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn