IV DIOSCORUS

(1) Early Years

(1.1)

The generally accepted date for the birth of Flavius Dioscorus is around A.D. 520.

Unlike his father who had to earn the status designation Flavius, Dioscorus always appears in the papyri in possession of

that title (whenever a title is expected). Like sons in other

well-to-do families in the early Byzantine period, Dioscorus probably studied

law abroad. Although there is no evidence, Alexandria is the most likely place

for him to have gone. MacCoull suggests that John Philoponus, the famous

Neoplatonic Christian philosopher, was one of his teachers.

(1.2) Back home in Aphrodito, Dioscorus married—the name of his wife has not survived—and had children. The documents clearly show that his family’s financial wellbeing and safety were a constant concern.

(1.2) Back home in Aphrodito, Dioscorus married—the name of his wife has not survived—and had children. The documents clearly show that his family’s financial wellbeing and safety were a constant concern.

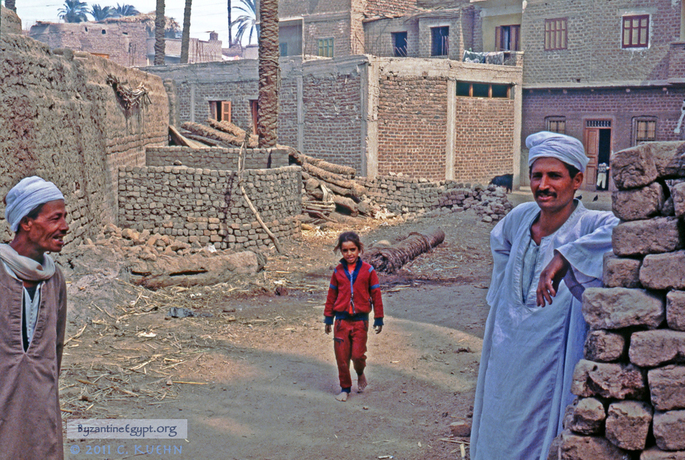

"Little Red." Kom Ishqaw (Aphrodito), Egypt. Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn

Like his father, Dioscorus

embarked on a busy career. Keenan lists “involvement in local ‘politics,’ acquisition,

leasing and management of agricultural land (his own and others’), defending

his own property rights and his village’s claim to rightful collection of its

own taxes, free of the pagarch’s interference (autopragia).” Dioscorus’s first dated appearance in the papyri is in

the year 543 (P.Cair.Masp. I 67087),

when he had the assistant of the defensor

civitatis of Antaeopolis personally examine the damage done by a shepherd

and his flock to a field of crops. The land was under his care, but owned by the

Monastery of Apa Sourous. During the years 543 to 547, the papyri show

Dioscorus purchasing wool, making a loan to two Aphroditan farmers, leasing

land to a priest and his brother, and having land ceded to him from another

priest, Jeremiah. In August of 547, Dioscorus leased one aroura of land to the

deacon Psais. This document (P.Cair.Masp.

II 67128) indicates that Dioscorus had by then attained the office of headman of

Aphrodito.

"Headman's Door." Kom Ishqaw (Aphrodito), Egypt.

Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn

Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn

(2) Problems with the Pagarchs

(2.1)

After his father’s death in 546/7, problems with the pagarchs intensified.

Dioscorus wrote a petition to the emperor Justinian and a formal explanation of

the problem to the empress Theodora, Aphrodito’s special patron. Copies have

survived. The former, P.Cair.Masp. I

67019 v (in poor condition), discusses Aphrodito’s autopragia status and mentions the pagarch Julian (l. 17). The

latter, P.Cair.Masp. III 67283,

paints a gloomy but generally nonspecific picture of the tax conflict. The

petitioners, representing much of the male population of the village and

including ecclesiastics from several churches in Aphrodito, begin with the

complaint that a nobleman has overstepped his powers by threatening to bring

them, the petitioners, before the pagarch of Antaeopolis in the matter of the

yearly assessment. Since Aphrodito, however, has the right of autopragia, the correct authority in

their case would be the duke. Dioscorus then depicts the state of affairs at

home. After raids by barbarians, the villagers were trying to lead a quiet and

good life. But like a plague, the pagarch and his cohorts attacked. “This papyrus

is not able to contain all the unspeakable injuries and injustices, except

to describe them in an unbroken wail.” Dioscorus then declares that “the one,

only, sole thing we have left is hope,” which is a literary allusion to Hesiod’s

farming epic Works and Days 96. And the

petitioners conclude by invoking the healing hand of the empress and the

ecclesiastical authorities.

(2.2) Although carefully and artistically composed, the explanation to the empress and the petition to the emperor seem to have had no effect. So in 551, three years after the death of Empress Theodora, and ten years after his father Apollos’ trip, Dioscorus was compelled to go to the capital of the empire with a contingent of at least three Aphroditans. The fact that Aphrodito sent a group of representatives all the way from Egypt to Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) makes clear that the grievances must have been serious. Dioscorus may have spent three years negotiating their problems in the “queen of cities”. Concerning the object of the trip, the delegation from Aphrodito finally obtained an imperial rescript, a draft of which has survived among Dioscorus’s papers. In it, Dioscorus states that while his father had been in Constantinople because of grievous injustices, a certain Theodosius took advantage of his absence and collected the taxes. Theodosius turned nothing over to the provincial treasury, and the village was still being held responsible for the taxes. Dioscorus had gone once already to Constantinople and had obtained a rescript, which was then ignored by Theodosius. Now in the rescript of 551, Dioscorus requests that the matter of the first rescript be brought to completion. And finally, he claims that Julian, the pagarch of Antaeopolis, was trying to bring Aphrodito under the control of his own pagarchy. The emperor replies to the charges by instructing the duke of the Thebaid to examine the issues and, if justified, to stop the pagarch’s aggression.

(2.2) Although carefully and artistically composed, the explanation to the empress and the petition to the emperor seem to have had no effect. So in 551, three years after the death of Empress Theodora, and ten years after his father Apollos’ trip, Dioscorus was compelled to go to the capital of the empire with a contingent of at least three Aphroditans. The fact that Aphrodito sent a group of representatives all the way from Egypt to Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) makes clear that the grievances must have been serious. Dioscorus may have spent three years negotiating their problems in the “queen of cities”. Concerning the object of the trip, the delegation from Aphrodito finally obtained an imperial rescript, a draft of which has survived among Dioscorus’s papers. In it, Dioscorus states that while his father had been in Constantinople because of grievous injustices, a certain Theodosius took advantage of his absence and collected the taxes. Theodosius turned nothing over to the provincial treasury, and the village was still being held responsible for the taxes. Dioscorus had gone once already to Constantinople and had obtained a rescript, which was then ignored by Theodosius. Now in the rescript of 551, Dioscorus requests that the matter of the first rescript be brought to completion. And finally, he claims that Julian, the pagarch of Antaeopolis, was trying to bring Aphrodito under the control of his own pagarchy. The emperor replies to the charges by instructing the duke of the Thebaid to examine the issues and, if justified, to stop the pagarch’s aggression.

(2.3)

A closer examination of this and the other documents surrounding the visit to

the capital reveals Dioscorus’s tact as a lawyer and the persistence of the

tax-crimes against Aphrodito. Several documents dealing with the confiscation

of tax money by Theodosius have been found among the Dioscorian papers.

Although the nature of their relationship to one another cannot be established

with certainty, Richard Salomon offers a good examination of the evidence and a

tentative chronology:

|

Around 548, the year of Theodora’s death, Dioscorus went

to Constantinople with a complaint against Theodosius for having stolen money

under the pretext of collecting taxes. The exact office of Theodosius is not

known: the surviving papyri call him simply the

most magnificent Theodosius. Salomon suggests that Dioscorus, a shrewd

lawyer, during his first visit in 548 took two routes simultaneously. He first

pleaded his case to the curator of the imperial house and

elicited a letter to the duke of the Thebaid to settle the difficulty (P.Hamburg Inv. No. 410). Later during

the same trip, Dioscorus was able to obtain a rescript from the imperial

cabinet (P.Cair.Masp. I 67029). The

lawyer’s intention was to try first a gentle persuasion of the duke; and if the

attempt should fail, Dioscorus had the emperor’s order in reserve. Both attempts

obviously failed. Theodosius was able to evade the imperial orders and kept the

money.

|

Detail from a sixth-century mosaic of

Empress Theodora and her court. |

Court of Emperor Justinian with (right) archbishop Maximian and (left) court officials

and Praetorian Guards. This and the mosaic above were completed before 547 and are

in the Basilica of San Vitale at Ravenna, Italy.

and Praetorian Guards. This and the mosaic above were completed before 547 and are

in the Basilica of San Vitale at Ravenna, Italy.

(2.4) So in 551 Dioscorus returned to Constantinople with a delegation from Aphrodito and obtained a letter from one of the highest officials of the empire (perhaps the Praefectus Praetorio Orientis) containing a personal recommendation to the duke (P.Geneva Inv. No. 210). Dioscorus also obtained a more strongly worded imperial rescript (P.Cair.Masp. I 67024) addressed to the duke of the Thebaid and requesting him to take care of the previous imperial command. None of the surviving imperial documents is an original: the original rescripts would have been turned over to the duke. But Dioscorus’s archive contains two letters which stem from the imperial palace and which are originals. Whether or not the matter with Theodosius was ever settled cannot be determined from the papyri. The second letter and the second imperial rescript, however, may have had a temporary effect on the pagarch. There is no indication of additional aggression by a pagarch against Aphrodito until after the death of Justinian the Great (565).