(1) Discovery - continued

(1.6)

Jean Maspero discovered that the literary and documentary papyri of the

1905–7 excavations at Kom Ishqaw had belonged to a certain Flavius Dioscorus, who

had lived during the sixth century A.D. Some of the documents, accounts, and

letters concerned his family and their property. Others concerned the village of

Aphrodite. (During the pharaonic era, the inhabitants of Kom Ishqaw had worshipped Hathor, the goddess of love. Later, the Greeks associated Hathor with Aphrodite and called the place Aphroditopolis. Historians now refer to the village as Aphrodito.) Some more documents involved the neighborhood and had been composed or acquired by Dioscorus during his

career as lawyer and headman of Aphrodito. And still other papers had been brought

back from Antinoöpolis, the principal city of the Thebaid region in southern

Egypt. Dioscorus had lived and worked there for seven years.

"Wind from the Nile." Kom Ishqaw (Aphrodito), Egypt. Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn

(2) Dispersal

(2.1)

Many of the papyri from the Dioscorian archive apparently had been removed and

concealed before Lefebvre’s arrival. A large number of these (some threescore

papyri) were purchased by the British Museum in 1906 and 1907, and edited by

Harold Idris Bell in a single volume, P.Lond.

V (1917). The University of Florence purchased still another score of papyri

between 1905 and 1907. Girolamo Vitelli edited many of these in P.Flor. III (1915). In fact, the first

publication of a document from the Dioscorian archive was a divorce contract

published in 1906 as P.Flor. I 93. In

addition, there were clandestine excavations at Kom Ishqaw and the discoveries

were privately sold. The end result was that papyri which had once belonged—in

Bell’s words—“to a single ‘muniment room,’ that of the poet Dioscorus,” became

dispersed throughout the Western Hemisphere. They can now be found in Cairo and—in the words of

James Keenan, an historian of Byzantine Egypt—“in Alexandria, Aberdeen, Cologne, Hamburg, Berlin,

Erlangen, Heidelberg, Florence, Ghent, Geneva, Paris, Strasbourg, Vienna,

Princeton, Michigan, and the Vatican—and even this list may not be exhaustive.”

(2.2) As the archive was spread around the world, parts of what had been a single document or single poem turned up in different collections. An example of the capriciousness of the dispersal of the Dioscorian archive is the hexameter panegyric (“poem of praise”) to John, P.Berol. 10580. Although first published in Berlin in 1907 as BKT V 3, it was augmented in 1936 by the addition of an iambic prologue that was among the Cairo papyri published by Maspero in 1916. Another example is the beautifully scripted encomium to Romanus (Heitsch 12, Fournet 4). The hexameter section with a column of words from the iambic prologue was published with the London collection in 1917 and 1927 (first a description of the papyrus as P.Lond. V 1817; later, the text and a photo as P.Lond.Lit. 98). The rest of the iambic prologue was not found until 1940, when P. Collart published the papyrus collection of Théodore Reinach (P.Rein. 2070). Still another example and “no doubt the most striking single instance of the archive’s dispersal,” writes Keenan, “was revealed in the 1976 publication by the late Rev. J. W. B. Barns of a papyrus owned by Dr. W. M. Fitzhugh of Monterey, California—the upper half of a document whose lower half was among the Cairo Museum papyri published by Maspero in 1911.”

(2.2) As the archive was spread around the world, parts of what had been a single document or single poem turned up in different collections. An example of the capriciousness of the dispersal of the Dioscorian archive is the hexameter panegyric (“poem of praise”) to John, P.Berol. 10580. Although first published in Berlin in 1907 as BKT V 3, it was augmented in 1936 by the addition of an iambic prologue that was among the Cairo papyri published by Maspero in 1916. Another example is the beautifully scripted encomium to Romanus (Heitsch 12, Fournet 4). The hexameter section with a column of words from the iambic prologue was published with the London collection in 1917 and 1927 (first a description of the papyrus as P.Lond. V 1817; later, the text and a photo as P.Lond.Lit. 98). The rest of the iambic prologue was not found until 1940, when P. Collart published the papyrus collection of Théodore Reinach (P.Rein. 2070). Still another example and “no doubt the most striking single instance of the archive’s dispersal,” writes Keenan, “was revealed in the 1976 publication by the late Rev. J. W. B. Barns of a papyrus owned by Dr. W. M. Fitzhugh of Monterey, California—the upper half of a document whose lower half was among the Cairo Museum papyri published by Maspero in 1911.”

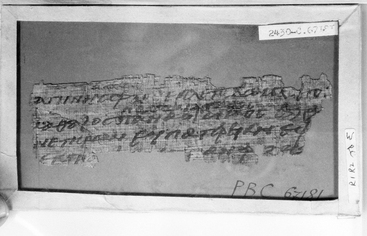

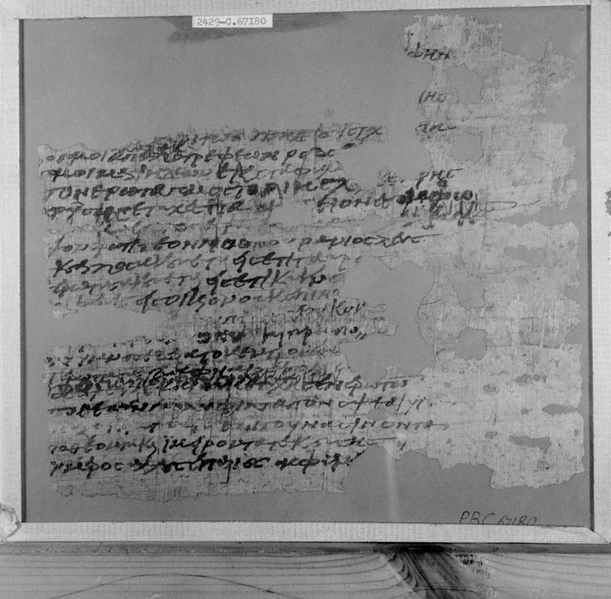

Top: P.Cair.Masp. II 67181 (= Heitsch 22, Fournet 33

verses 6, 7, 5, 4). This is the top portion of the papyrus. Bottom:

P.Cair.Masp. II 67180 (= Heitsch 22 cont., Fournet

33 cont.). The right side of the poem is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The

left side of the poem (not pictured) is now in the British Library in London (P.Lond.

V 1819). The poem was written by Dioscorus to celebrate the wedding of Matthew. Photos © 2011 C. Kuehn

(2.3) In his publication of the Dioscorian archive at the Egyptian Museum, Jean Maspero divided the Greek papyri into five categories: administrative; financial; private documents from Aphrodito and the Antaeopolite nome; private documents from Antinoöpolis and other neighboring cities; and literary fragments. Most of these documents were composed in the sixth century A.D. during the reigns of Justin I, Justinian, and Justin II. Some of the more interesting non-documentary items include—in addition to the Menandrian codex—the remains of a codex of Homer’s Iliad and fragments of possibly an Aristophanic comedy (or comedies), a biography of the Athenian orator Isocrates, a Greek-Coptic glossary, a letter from the sixth-century A.D. philosopher Horapollon, metrological charts, and conjugations of Greek verbs. A Latin-Greek-Coptic glossary may also have belonged to Dioscorus. It is without doubt one of the richest and most important papyrological finds ever. “If the still scanty band of papyrologists,” Bell wrote in 1925, “should ever compile a calendar of their own, it would be necessary to assign a red letter day to the memory of Dioscorus.”

"Still Digging." Kom Ishqaw (Aphrodito), Egypt. Photo © 1995, 2011 C.Kuehn