III APHRODITO,

APOLLOS, AND RELIGIOUS LIFE

(1) Village of Aphrodite

(1.1)

“The village of Aphrodite,” Keenan wrote, “was more than an ordinary

Byzantine Egyptian village.” During dynastic times and into the early Roman

period, Dioscorus’s village had been the capital city of its own nome, the

tenth of Upper Egypt. (A nome was a

governmental district similar to a county in the United States. Upper Egypt was in the south, which is higher in altitude

than the north.) Perhaps at the beginning of the Byzantine period and

certainly before the sixth century A.D., the tenth nome was merged with the

Antaeopolite nome across the Nile River, and Aphroditopolis lost its status as a

capital and its designation as a polis

(“city”). It was now the village of Aphrodite, or simply Aphrodito.

At the Temple of

Hathor, goddess of love and beauty, stands a relief of the Egyptian god Bes.

He was the protector of women in labor and children. He eventually became the enemy of all evil.

Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn

He was the protector of women in labor and children. He eventually became the enemy of all evil.

Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn

During the

fifth century, moreover, the administrative structure of Upper Egypt underwent

a transition. The areas of a nome outside the capital city were divided into

pagi (“districts”) and placed under

the jurisdiction of a pagarch. The pagarch

had the responsibility to collect the public taxes from the villages under

his or her jurisdiction. Aphrodito, however, received from the emperor the

privilege of autopragia, which meant

that the village was given the right to collect its own imperial taxes and

deliver them directly to the provincial treasury. Thus Aphrodito was outside

the jurisdiction of the pagarch with respect to public taxes. The surviving

documents do not disclose exactly when Aphrodito received this special

privilege, but for several generations (Dioscorus insists) it faithfully met

its public tax requirements. And in the mid-sixth century, for reasons unknown,

Aphrodito was enjoying the special patronage of the empress Theodora.

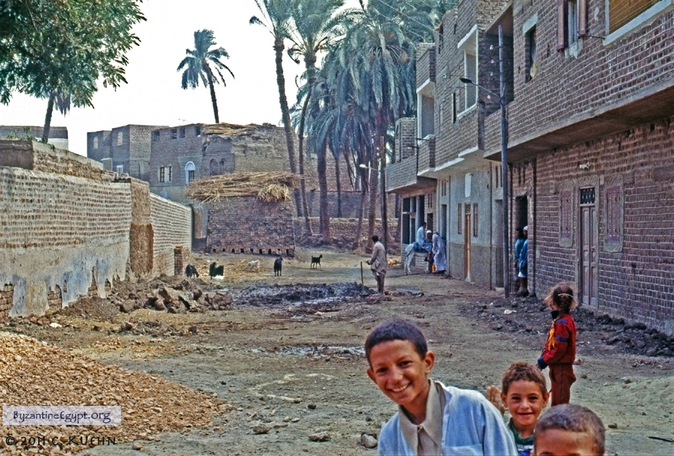

"Welcome Committee." Kom Ishqaw (Aphrodito), Egypt. Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn

(1.2)

The pagarchs living in Antaeopolis, now the capital city of the merged nome,

seem to have resented the village’s autopragia, and the papyri show that the

pagarchs often violated Aphrodito’s special tax-status. The pagarchs were able

to do so with some degree of impunity because the pagarchs were, in effect, powerful. The pagarch’s official responsibilities, as mentioned above,

were the financial affairs of a nome, especially the taxes. The pagarch came

from the nobility of the area and always had an honorific title. He or she was

probably selected by the nobles, bishop, and corn-buyer of the capital city of

the nome. And the selection could have been based upon the amount of land the

candidate owned (to cover any delinquencies in the tax collection). Once a

candidate was selected, he or she was appointed by the praetorian prefect—an

appointment that had to be confirmed by the emperor. Once the appointee was in

office, the reigning duke of the region could issue orders to him or her and

express any dissatisfaction to the emperor, but the duke could not remove the

pagarch. And while the papyri show that there was a rapid turnover of dukes,

the pagarchs of the nomes under his jurisdiction tended to remain in office for

a long time. The office was sometimes passed on hereditarily. To enforce his

work, the pagarch could and did employ local policemen, men from the provincial

government, the private guards of large estate owners, and soldiers. Thus the

pagarch—because of personal wealth, strong ties to the nobility of the

community, the appointment

by Constantinople, a relatively long term in office, and an armed “backup”—was a person whose disfavor was avoided. The conflicts that developed

between Aphrodito and the pagarchs were neither trivial nor bloodless.

"Fence." Kom Ishqaw (Aphrodito), Egypt. Photo © 1995, 2011 C. Kuehn